Fresh out of stories praising the brave freedom fighters who overthrew the warlord who kept Egypt out of truly pointless and destructive wars, the mainstream media is now feasting on the comically lugubrious and sordid details of the gang-rape of anchor Lara Logan.

Fresh out of stories praising the brave freedom fighters who overthrew the warlord who kept Egypt out of truly pointless and destructive wars, the mainstream media is now feasting on the comically lugubrious and sordid details of the gang-rape of anchor Lara Logan.

This stuff reads more like porn than any kind of respectable journalism, but what is most interesting is that moments after the echoes of their praise died on the rebar walls, they’re pointing out the problem with the Egypt revolution, and revolutions in general: they produce an anarchy in which the most fanatical and venal elements prevail.

“In the crush of the mob, [Logan] was separated from her crew. She was surrounded and suffered a brutal and sustained sexual assault and beating before being saved by a group of women and an estimated 20 Egyptian soldiers.

A network source told The Post that her attackers were screaming, “Jew! Jew!” during the assault. And the day before, Logan had told Esquire.com that Egyptian soldiers hassling her and her crew had accused them of “being Israeli spies.” Logan is not Jewish.

Her injuries were described to The Post as “serious.”

But after she was assaulted, Logan went back to her hotel, and within two hours — sometime late Friday and into early Saturday — was flown out of Cairo on a chartered network jet, sources said.

She wasn’t taken to a hospital in Egypt because the network didn’t trust local security there, sources said.

And neither CBS nor Logan reported the crime to Egyptian authorities because they felt they couldn’t trust them, either, the sources said. “The way things are there now, they would have ended up arresting her again,” one source said. – NY Post

Remember when Grandma would tell you to go to church or school, and you’d ask why, and she’d say it was so you could fill your social role, and you’d ask why, and finally she’d say that you just had to do it or social order would unravel and we’d have anarchy?

This is what she was talking about.

Social order is what keeps us communicating when we differ, and gives us methods of finding leadership without resorting to the kind of simian violence that we see in ghettoes and riots. Without imposing this order on ourselves, we tend toward an all-consuming desire to destroy anything but ourselves. We also like to have justifications like “freedom fighting for democracy” to cover our baser motives, like theft, rape and violence.

When we in the West talk about our values and the importance of public civility, we’re talking about avoiding this kind of situation. Yet we don’t avoid it always. What happened in Russia in 1917, and France in 1789, was very similar: the masses ran riot with their emotions and as a result, murdered and destroyed extensively at the expense of centuries of culture and social order.

No one wants to admit this, but the path of liberalism is straight toward this disorder. Liberalism is a spectrum from Social Democrat to Communist to Anarchist, and it tends toward the latter because it is a philosophy based in the individual negating obligations outside of the self. This atomized individual casts off first the shackles of leaders above, then of social convention, then even of biological convention and common sense. Eventually, they are the violent rabble: a surging horde of self-serving people united under the social pretense that they’re bringing equality to all.

Is there an alternative?

The old ways are returning. They are both past and future, because unlike “theoretical” philosophy such as liberalism, they are based in a study of human societies through history, and develop a philosophy of what ideas produce which results. Where liberalism is an emotional and social response to the question of self-government, the old-new ways are a scientific one. Study what people did, what response was created, and then pick what of that result you want to retain.

Monarchists have held a founding congress of their new party in Moscow. The Tsarist Russia party sees restoring the monarchy in the country as one of its main strategic purposes.

On Sunday, 147 delegates from 46 Russian regions gathered in the capital to create the new party, reports Rossiyskaya Gazeta daily. A black-yellow-white tricolor was chosen as its flag and a double-headed eagle as its emblem. The slogan for the gathering was “Tsar is coming to Russia and you should lead the people towards Tsar”.

Historian Dmitry Merkulov, who was elected the chair of Tsarist Russia, said that the constitution could be changed in a democratic way, by calling a Zemsky Sobor (Council of all Lands), or a parliament of the feudal Estates type, similar to the one that was first established by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century. “And Zemsky Sobor could choose a monarch,” Merkulov explained.

The new party also approved its charter, which was published on the Tsarist Russia’s website. Among its main purposes, the movement names molding public opinion on the necessity to go back to “monarchist rule, as is traditional for Russia,” educating citizens in “monarchist spirit,” and, also, taking part in parliamentary and presidential elections. – RT

You don’t come to this blog to have me bloviate socially-correct popular “truths” that are nothing more than a salesperson’s illusion writ large. Instead, you come here for the skinny, or maybe the typos. Let’s look critically at humanity.

Most of our people cannot think more than two weeks ahead. They have poor impulse control. They do not consider others before themselves; in fact, they don’t consider them at all. Selfish and wasteful, they move through life like bulls in a china shop, chasing desires and pleasures and leaving behind mountains of landfill.

When they get all good and riled up and really wreck something, they find the biggest source of power nearby and blame it, and then try to stage a revolution. Their hobbies include rutting recklessly and overpopulating their lands, as happened in both revolutionary France and Egypt, so that they have an excuse for more rioting.

Monarchy imposes an order on this that is not based on popularity. Kings do not honestly care what the proles think of their rules, because they know the proles are unable to think past the next two weeks of pulling turnips, nailing barmaids and drinking cheap wine until they vomit glassine sheaves of bile. Monarchy is what happens when you set up a hierarchy that moves the best leaders toward the top and makes them custodians of the society at large.

The opposite extreme is populist democracy (1 person = 1 vote) which tends to stretch the revolution over centuries, gradually peeling back layers of social order until you have anarchy. First the people want basic rights, then they expand the definition of those rights, and finally they make a society where people trade illusions around in order to keep from challenging themselves at all.

Look around your average workplace, for example. Do these people actually do much of anything? They each have a role, and those roles might be at some stage vital, but generally it’s a small amount of real work stretched between many people so that each person must succumb to the mind-numbing boredom of meetings, paperwork, irrelevant tasks and busy work. No wonder our society is miserable.

DOWNEY (KTLA) — An L.A. County employee apparently died while working in her cubicle on Friday, but no one noticed for quite some time.

51-year-old Rebecca Wells was found by a security guard on Saturday afternoon.

She was slumped over on her desk in the L.A. County Department of Internal Services.

The last time a co-worker saw her alive was Friday morning around 9:00 a.m., according to Downy police detectives. – KTLA

What a lonely existence we’ve made! But if Rebecca did a more important job, not everyone could be employed in relative ease. And people want jobs that are safe, stable and not very challenging, so everyone (roll your eyes like an implant in your brain just gave you a jolt as you say this) can participate. They don’t care if those jobs are boring. They’re more afraid of not being equal, or not being equal to a task.

If you wonder what the end stages of democracy are like, they’re this: the currency is overvalued, the jobs are created and ruled by red tape, no one speaks honestly, advertising fills your head with pleasant images while the civilization around you rots and eventually ends up in third-world status like other fallen empires. Then you get send out to the fields, but at that point you or your descendants are dumb as bricks, since anyone intelligent got weeded out by angry rioting mobs years before.

This is why people are rediscovering the old ways, and giving them new names and new contexts. The old ways worked. Here’s another example:

Herzl witnessed mobs shouting “Death to the Jews” in France, the home of the French Revolution, and resolved that there was only one solution: the mass immigration of Jews to a land that they could call their own. Thus, the Dreyfus Case became one of the determinants in the genesis of Political Zionism.

Herzl concluded that anti-Semitism was a stable and immutable factor in human society, which assimilation did not solve. He mulled over the idea of Jewish sovereignty, and, despite ridicule from Jewish leaders, published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State, 1896). Herzl argued that the essence of the Jewish problem was not individual but national. He declared that the Jews could gain acceptance in the world only if they ceased being a national anomaly. The Jews are one people, he said, and their plight could be transformed into a positive force by the establishment of a Jewish state with the consent of the great powers. He saw the Jewish question as an international political question to be dealt with in the arena of international politics. – JVL

But wait; wasn’t that the original idea behind civilization? That each state was one national group, and that they kept their culture, values, customs, language and heritage apart from others, for the most part? We moderns are so accustomed to stumbling around in ignorance that when we finally interpret the ideas of the past, or re-discover them, we find a light that was not so much hard to find as pushed aside in the belief it was antiquated, obsolete, ignorant or irrelevant.

As our societies spiral into anarchy and third world disorder, more people are detaching from the obsolete conventions of modernity and are instead embracing an entirely different view of society: it’s not about what individuals want to think is real, but about what is real. It’s not about different points of view, each of which is a separate valid existence, but about reconciling those points of view to find pragmatic solutions.

We had to sit through two weeks of Egypt coverage and fawning praise about how this is a new way and new light for the Middle Eastern country, only to finally discover that our carefully contrived terms were hiding instead something quite ancient. For all the happy language we heaped on the event, it was a loss of social order and a form of decay. Let’s hope the rest of us find this out in a way less painful than that which Lara Logan endured.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

El sitio (electrónico) WikiLeaks ha hecho un trabajo de salubridad pública al desvelar una gran cantidad de las vilezas de nuestros “grandísimos amigos americanos”. Quienes, por ejemplo, explotan a fondo –cuestión de juego limpio– el servilismo sarkozyano en beneficio propio (véase la página 4) (2).

El sitio (electrónico) WikiLeaks ha hecho un trabajo de salubridad pública al desvelar una gran cantidad de las vilezas de nuestros “grandísimos amigos americanos”. Quienes, por ejemplo, explotan a fondo –cuestión de juego limpio– el servilismo sarkozyano en beneficio propio (véase la página 4) (2).

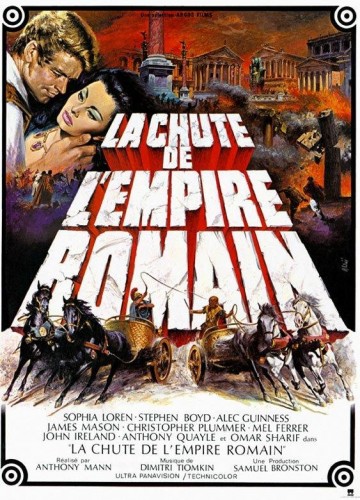

Fiction: en juillet 1940, Hitler parvient à forcer la main au général Franco qui laisse passer les troupes allemandes sur son territoire. Gibraltar tombe et les panzers, après avoir traversé le Maroc et l'Algérie, foncent sur Le Caire. 300.000 prisonniers français sont libérés et commis aux moissons. La popularité du vieux maréchal est au zénith. Un débarquement allemand a lieu en Irlande du Sud. Malte tombe aux mains des paras de la Luftwaffe de Goering. Churchill est mis en minorité et remplacé par Lord Halifax, qui fait la paix, en échange des puits de pétrole du Moyen Orient, qui restent sous contrôle britannique. Pourquoi faire la guerre dans ces conditions? Le succès de l'opération Barbarossa est quasi complet et, rapidement, les troupes de l'Axe font jonction dans le Caucase. Par un coup d'audace inouï (Skorzeny?), Vladivostok tombe. C'est la panique au Japon, qui se rapproche des Américains. Dans l'Empire, c'est le délire: d'ailleurs, à Berlin, on joue Sartre à guichets fermés! Dans cette atmosphère de triomphalisme, l'épuration ethnique dont sont victimes les Juiffss prend heureusement fin et l'Empire favorisera même, pour gêner les Anglais, la naissance d'un Etat hébreu, armé par l'Allemagne. A Berlin, l'aile modérée menée par Bibbentrop, le cher Otto Tabetz, ou Krommel élimine les “natzis” forcenés. Une fausse explosion nucléaire, vers 1943, calme les Américains, qui se contentent d'armer la résistance soviétique (Staline combat toujours en Yakoutie). Une vraie bombe, que le Führer obtient grâce à ses réseaux d'espions (juiffss?) aux Etats-Unis, assure définitivement la neutralité américaine. Hitler meurt le 30 décembre 1946, à la veille du réveillon. Speer, l'amiral Panaris et surtout Gersdorff entreprennent une première “dénatzification” et, de 59 à 78, Stendel, le Führer suivant, proscrit le racisme et le remplace par le différentialisme critériologique: les Juiffss sont incités à collaborer ou à émigrer en Israël, où ils forment une tête de pont de l'Empire.

Fiction: en juillet 1940, Hitler parvient à forcer la main au général Franco qui laisse passer les troupes allemandes sur son territoire. Gibraltar tombe et les panzers, après avoir traversé le Maroc et l'Algérie, foncent sur Le Caire. 300.000 prisonniers français sont libérés et commis aux moissons. La popularité du vieux maréchal est au zénith. Un débarquement allemand a lieu en Irlande du Sud. Malte tombe aux mains des paras de la Luftwaffe de Goering. Churchill est mis en minorité et remplacé par Lord Halifax, qui fait la paix, en échange des puits de pétrole du Moyen Orient, qui restent sous contrôle britannique. Pourquoi faire la guerre dans ces conditions? Le succès de l'opération Barbarossa est quasi complet et, rapidement, les troupes de l'Axe font jonction dans le Caucase. Par un coup d'audace inouï (Skorzeny?), Vladivostok tombe. C'est la panique au Japon, qui se rapproche des Américains. Dans l'Empire, c'est le délire: d'ailleurs, à Berlin, on joue Sartre à guichets fermés! Dans cette atmosphère de triomphalisme, l'épuration ethnique dont sont victimes les Juiffss prend heureusement fin et l'Empire favorisera même, pour gêner les Anglais, la naissance d'un Etat hébreu, armé par l'Allemagne. A Berlin, l'aile modérée menée par Bibbentrop, le cher Otto Tabetz, ou Krommel élimine les “natzis” forcenés. Une fausse explosion nucléaire, vers 1943, calme les Américains, qui se contentent d'armer la résistance soviétique (Staline combat toujours en Yakoutie). Une vraie bombe, que le Führer obtient grâce à ses réseaux d'espions (juiffss?) aux Etats-Unis, assure définitivement la neutralité américaine. Hitler meurt le 30 décembre 1946, à la veille du réveillon. Speer, l'amiral Panaris et surtout Gersdorff entreprennent une première “dénatzification” et, de 59 à 78, Stendel, le Führer suivant, proscrit le racisme et le remplace par le différentialisme critériologique: les Juiffss sont incités à collaborer ou à émigrer en Israël, où ils forment une tête de pont de l'Empire.  L'Empire est résolument non humaniste et rejette sagement les droits de l'homme, qui ne sont jamais que “les droits du client”: “droit de chier des litanies de progénitures débilo-crédulo-proliférantes, pulluliques, malsaines, ivres de tuer leur prochain ou de leur passer la Grande Maladie”. Car la Maladie, venue de l'Ouest est interdite dans l'Empire: un corps d'élite veille et nettoie, liquidant impitoyablement malades infiltrés par les démothalassocrates, agents d'influence de la pourriture utilitairo-protestante et militants nationalistes (des Gagaouzes aux Vourdalaks). Pas question d'affaiblir l'Empire! Les chrétiens, et les croyeux

L'Empire est résolument non humaniste et rejette sagement les droits de l'homme, qui ne sont jamais que “les droits du client”: “droit de chier des litanies de progénitures débilo-crédulo-proliférantes, pulluliques, malsaines, ivres de tuer leur prochain ou de leur passer la Grande Maladie”. Car la Maladie, venue de l'Ouest est interdite dans l'Empire: un corps d'élite veille et nettoie, liquidant impitoyablement malades infiltrés par les démothalassocrates, agents d'influence de la pourriture utilitairo-protestante et militants nationalistes (des Gagaouzes aux Vourdalaks). Pas question d'affaiblir l'Empire! Les chrétiens, et les croyeux

On connaît le refrain, il scande un demi-siècle d’antifascisme parodique. On le croyait inusable, mais il a vieilli. Il faut dire que la bête immonde a profondément mué. Elle ne porte plus des cornes, mais des Ray Ban. La chirurgie esthétique a adouci ses traits. Chemin faisant, on est passé des années 40 au CAC 40. C’est beaucoup plus fun. Il manquait un nom à cette nouvelle bête. Raffaele Simone lui en a trouvé un, c’est « le Monstre doux », titre de son dernier livre***, qui a fait pas mal de remous en Italie à sa sortie en 2009, dans un pays berluscosinistré. L’ouvrage n’est pas sans intérêt, même s’il n’apporte rien de nouveau, en tout cas rien qui n’ait déjà été dit par Tocqueville. Ce monstre doux, c’est l’Occident qui virerait à droite, selon Simone, mélange de Big Brother et de Mickey Mouse.

On connaît le refrain, il scande un demi-siècle d’antifascisme parodique. On le croyait inusable, mais il a vieilli. Il faut dire que la bête immonde a profondément mué. Elle ne porte plus des cornes, mais des Ray Ban. La chirurgie esthétique a adouci ses traits. Chemin faisant, on est passé des années 40 au CAC 40. C’est beaucoup plus fun. Il manquait un nom à cette nouvelle bête. Raffaele Simone lui en a trouvé un, c’est « le Monstre doux », titre de son dernier livre***, qui a fait pas mal de remous en Italie à sa sortie en 2009, dans un pays berluscosinistré. L’ouvrage n’est pas sans intérêt, même s’il n’apporte rien de nouveau, en tout cas rien qui n’ait déjà été dit par Tocqueville. Ce monstre doux, c’est l’Occident qui virerait à droite, selon Simone, mélange de Big Brother et de Mickey Mouse.

Thus the first priority was to keep these people as safe as possible from another slaughter. At the same time, Pétain hoped for a future renaissance through a “national revolution.” He has been attacked for that. Admittedly, all would be mortgaged by the Occupation. But really he had no choice. The “national revolution” was not premeditated. With all its ambiguities, it emerged spontaneously as a necessary remedy to the evils of the previous regime.

Thus the first priority was to keep these people as safe as possible from another slaughter. At the same time, Pétain hoped for a future renaissance through a “national revolution.” He has been attacked for that. Admittedly, all would be mortgaged by the Occupation. But really he had no choice. The “national revolution” was not premeditated. With all its ambiguities, it emerged spontaneously as a necessary remedy to the evils of the previous regime.